Bruce C Carleton

Professor and Chair, Division of Translational Therapeutics,

Department of Paediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia

Pharmacovigilance has come a long way in helping us link medicines to their side-effects; with the help of pharmacogenomics it can go even further.

Pharmacovigilance has a long and storied history, and like all disciplines in medicine and health care, it continues to improve and become more valuable over time. Methods for identifying links between drug use and adverse outcomes have improved, and data collection procedures for drug-induced adverse events have become more comprehensive. Analysis of such data has also improved. But can data alone be used to find solutions to prevent many serious and well-known adverse drug reactions (ADRs)? Warnings are important components of reducing harm, but the physiological mechanism that underlies an adverse drug reaction often remains elusive.

Knowing that a drug causes an adverse reaction is only part of the solution. In many cases, avoiding a drug or specific drug dose that increases risk of harm is not possible as this may be the only treatment available for a serious disease, for example, cancer, disabling arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and many other medical conditions.

Furthermore, causality is hard to prove. Temporal relationships between a drug and adverse event may help, but they aren’t the only criteria to determine cause and effect. Scoring systems for assessing causality like the Naranjo scale can also be helpful, but are of limited value when things like de-challenging and re-challenging are not viable options due to the severity of the initial adverse reaction. There is also the common problem of polypharmacy, where a patient taking multiple drugs complicates the ability to determine which one is responsible for an ADR. Often we are left with an adverse event having a “possible or probable” link to a drug exposure, but not a “definite” one.

This is where pharmacogenomic information can help. The human genome is a window into the biology of adverse events since pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects are controlled by processes encoded by genes. A pharmacogenomic study that examines genetic traits of patients exposed to the same drug with and without a specific toxicity can help in determining the mechanistic basis of drug toxicity – the pathway of harm. Once we know the pathway(s), we can study how to prevent them. In many cases, genetic traits can be protective – so enhancing these naturally-occurring protective mechanisms in those without inborn protection is also possible.

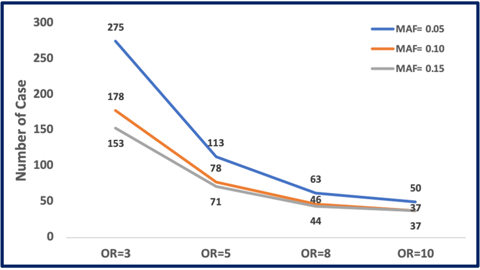

Saliva is a biological fluid from which we can extract DNA for such studies. It can be collected easily from patients, stored without refrigeration, and remains stable for years. So it’s definitely possible to obtain biological samples along with detailed and thorough reports of ADRs as part of the data collection process. Given the ease of collection of this kind of data, why isn’t more work being done to define this new joint field of study? That is, a pharmacogenomic linking of gene variants known to affect a drug’s pharmacokinetic and/or pharmacodynamic properties with the careful and rigorous data collection procedures of pharmacovigilance? The numbers of patients needed for such studies are not unreasonable to get started and effect sizes are generally quite strong (odds ratios of three or more). These studies are powered for detecting genetic variant frequencies, known as minor allele frequencies (MAF). A MAF of at least five percent makes the most sense since rarer variants would be hard to find even with large sample sizes. As you increase the frequency of the genetic variant responsible for a given ADR, the sample size goes down, as can be seen in figure 1.

We are fortunate that drug development, regulatory review, and ongoing surveillance are quite effective in ensuring most drugs are safe for the majority of patients. Yet serious harm does occur and knowing why and in whom such reactions are likely to occur cannot be fully elucidated with clinical variables alone. It’s time to enhance methods of pharmacovigilance and focus on solution finding, not just problem identification. Warning patients is important. Actually solving drug toxicity problems is even better.

Disclaimer: In addition to the standard Uppsala Reports disclaimer, it should be noted that any opinions or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of UMC. In particular, the field of pharmacogenomics lies outside UMC’s core activities and UMC makes no recommendations as to issues such as genome screening or other related practices.

Read more:

For an introduction to pharmacogenomics and its use in pharmacovigilance, see an earlier Uppsala Reports article on the subject:

“To genotype or not to genotype, that is the question”, Uppsala Reports

Over 500 attendees from 80+ countries met in Cairo at ISoP 2025, reflecting on pharmacovigilance progress and shaping strategies for its future.

10 December 2025

Medical devices are everywhere, but monitoring their safety is complex. Omar Aimer discusses the unique challenges of device pharmacovigilance and what needs to change.

29 January 2026

Patient engagement was a hot topic at the fireside chat held during this year’s ISoP mid-year symposium.

24 June 2025