Bob Allkin

Programme Manager Science, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Illustration: Zellout

Inconsistent use of names for medicinal plants and plant-based drugs can have serious health consequences and impede efforts to analyse adverse reactions to herbal medicines.

More than 100 people in Belgium were prescribed slimming pills containing fang ji, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), in 1998. Severe nephropathy ensued, with most patients requiring dialysis. The clinic had dispensed the wrong product, unaware that ‘fang ji’ refers to TCM drugs derived from two different plants: Stephania tetrandra and Aristolochia fangchi. Subsequent reports demonstrated the same substitution had occurred in other countries. Ambiguity of herbal drug names is surprisingly widespread, the name ‘ginseng’ being associated with drugs derived from at least 18 plants with differing chemistries. Failing to deal with this ambiguity in labelling, regulation, and quality control clearly has serious health consequences.

Growing international use and trade in herbal products increases the urgency for professionals to address this issue. Pharmacovigilance professionals need accurate names for plant-based products to undertake effective signal analysis. Similarly, clinical trials must know which plant-derived drugs are taken by participants. Those writing monographs or framing regulations must be precise as to which plant is intended, and be aware of all its possible synonyms if they are to locate all relevant publications and adverse reaction records. Unambiguous labelling of plant materials and health records is the first step towards safer use and more effective authentication and quality control.

An astonishing number of medicinal plants are used worldwide, and international trade in herbal drugs and plant-based food supplements is growing. WHO estimated that the trade in TCM products alone was worth US$83 billion in 2012, and report that 90% of Germans use herbals. Although most formal healthcare systems continue to neglect them, a few countries are now integrating ‘traditional’ plant-based drugs into mainstream medicine, particularly to treat chronic conditions. Millions of people, especially in rural communities in parts of Africa, Asia and South America, nevertheless rely on traditional remedies

for their primary healthcare needs.

“Only 16% of medicinal species are under regulatory control, despite the popularity of herbal remedies.”

Knowing exactly how many medicinal plants are used is complicated, as most plants are known by multiple names, causing double counting. In their 2017 State of the World’s Plants report, Kew Gardens, a botanical research institute managing global taxonomic references, provided a reliable lower limit of 28,187 medicinal species cited in approximately 150 major pharmacopoeias and medicinal references.

This study also showed that only 16% of medicinal species are under regulatory control, despite the popularity of herbal remedies. Indeed, the number of species described within pharmacopoeias fell during the 20th century, with the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia, for example, citing 196 plants in 1926 but only 11 in 1996. Similar trends occur in European pharmacopoeias, despite recent inclusion of TCM plants. Why should this be? Several reasons exist. Some herbals simply fell out of favour as more targeted drugs became available. Gathering the scientific evidence required of modern monographs can also be a challenge when working with herbals, which are more complex than pharmaceutical drugs and consist of multiple chemicals with multiple potential targets. Nevertheless, such drugs often remain in widespread use despite their removal from pharmacopoeias.

Plants and the drugs derived from them are referred to using common, pharmaceutical or scientific names. Common names like ‘ginseng’ are part of everyday speech; they vary from place to place and their meanings may change over time. A plant called ‘yarrow’ in some places is referred to as ‘millefeuille’ or ‘woundwort’ elsewhere (synonyms). A name like ‘bluebell’ may refer to one species in England and another in Scotland (homonyms). The multiplicity of names and their inconsistent use across countries and disciplines cause considerable confusion.

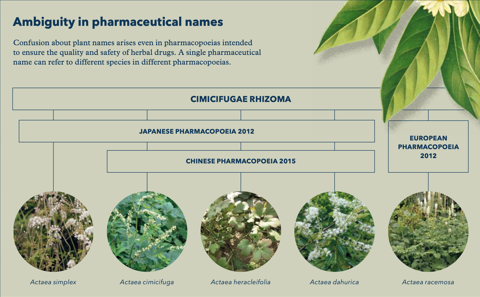

Pharmacopoeias offer detailed technical descriptions of how to prepare herbal drugs and should be precise about which plant to use. Sadly, this is not always the case. Some pharmacopoeias use common names, and many others employ pharmaceutical names – often confusingly written in Latin – indicating the plant part or the preparation to be used (e.g. ginseng radix rubra). Pharmaceutical names are under no formal control and often refer to drugs derived from different plants in different pharmacopoeias, or even different editions

of one pharmacopoeia.

Scientific plant names, in contrast, are formally controlled: their publication follows procedures established in the International Code of Nomenclature requiring, for example, that authors of new names cite the herbarium specimen(s) studied. These provide permanent physical evidence of the anatomy, chemistry, and DNA of plants carrying that name. Individual scientific names, written in full, are thus unambiguous and provide the only reliable way to refer to plants.

Obstacles exist, however, to using scientific names effectively. Non-botanists may be unaware of these issues, particularly the frequency with which plant nomenclature changes as understanding of taxonomic relationships improves. The misuse of scientific names by regulators, pharmacists, and pharmacovigilance staff can have serious consequences: ineffective regulation, misidentification, ambiguous publication, and even contradictory controls when regulators fail to appreciate that two names are synonyms for the same species.

1.6 million scientific plant names exist for 400,000 higher plants – 4 names per plant. Intensely studied medicinal plants have 14 synonyms on average (Achillea millefolium L., or ‘yarrow’, has 70!) preventing you from finding all publications for any plant.

10,000 changes to scientific plant names are published every year. Molecular and chemical studies offer new insights into plant relationships, requiring species to move between genera, be split, or merged.

4% of scientific names employ the same genus and species names, but were published by two authors independently to refer to two different plants. E.g. Illicium anisatum Lour. is star anise – a widely used condiment – while Illicium anisatum L. is a poisonous Japanese relative. Regulations citing Illicium anisatum with no author name are thus ambiguous.

Botanical databases offer alternative taxonomic opinions based upon different evidence, scope and purpose. Websites often copy data from others, but fail to update when the original is corrected. Rarely do these sources contain pharmaceutical or common names.

Kew’s Medicinal Plant Names Services (MPNS) addressed this confusion by capturing all pharmaceutical, common and scientific names employed for herbal drugs in 150 major medical references, regulatory data sets and pharmacopoeias. Each name was mapped to Kew’s botanical references to extract the current scientific name and all synonyms for each plant. MPNS can thus reliably count species and make links between pharmacopoeias that use different names for the same plant. The current version of MPNS, published in May 2017, contains 384,000 unique names for only 26,000 plants.

MPNS is updated regularly to reflect continuing improvement in Kew’s taxonomies, and a portal enables users to search with any name familiar to them, be alerted to any ambiguity, discover which pharmacopoeias or references cite each plant, and check which plant parts and names are cited. Onward links provide additional information about the plants, such as chemistry, authentication details or illustrations, and permit comprehensive PubMed searches. Searching PubMed directly with a single scientific name will, on average, retrieve 10-15% of records about that plant. Searching PubMed via the MPNS portal, on the other hand, uses all scientific synonyms simultaneously and retrieves all records about that species, irrespective of which scientific names were used in the original publications, which is especially useful for research applications and for tracking adverse reactions.

1. Do not use common or pharmaceutical names alone.

2. Always use the full scientific name: genus, species, subspecies and author.

3. Use the currently preferred scientific name and be aware of all its synonyms.

4. When in doubt, consult the following resources in this order:

i. Medicinal Plant Names Services

ii. Plants of the World Online

iii. The Plant List

Since MPNS can link terminologies from different regulators, it is used by a new ISO standard: the Identification of Medicinal Products (IDMP), devised to harmonise specifications for all medicinal products. MPNS provides a controlled vocabulary for plant names and plant parts, and a web service updates the vocabulary periodically as plant names change. MPNS has worked with other health agencies to validate and enrich their plant data, and it offers training in designing workflows and IT systems reflecting best practice. MPNS continues to add medicinal sources from other countries and seeks partners to expand its coverage of food supplements, cosmetics and plants causing poisoning or allergic reactions.

An old collaboration between Kew and Uppsala Monitoring Centre was reinvigorated by MPNS. For each of the approximately 4,000 different scientific plant names in the WHODrug dictionary, MPNS provided spelling corrections, the family name and the currently preferred scientific name and synonyms. This highlighted plants stored within VigiBase, the WHO global database of individual case safety reports, under multiple names, and enabled these to be linked to each other. The automatic validation saved effort, whilst increasing integrity and currency of plant data in VigiBase. Now UMC and MPNS wish to enrich VigiBase with full synonymy (so that users can find all relevant drug or adverse reaction records for signal analysis), enhance links to Kew’s data, and allow plant names in VigiBase to be periodically refreshed.

Overall, MPNS is facilitating effective international communication about herbal drugs. Reducing effort and duplication amongst health agencies, through use of the tools and data described, can prevent repetition of tragic cases like the 1998 fang ji mix-up in Belgium. However, management of adverse reactions for traditional plant medicines not covered by pharmacopoeias remains imperfect. Ideally, reports would ensure authenticity of plant materials and cite the scientific name, plant part, and dosage employed. Traditional remedies are the primary source of healthcare for millions of people who deserve that we give as much attention to these remedies, as to herbal products optionally used in the West.

Read more:

R Allkin et al., “State of the World’s Plants 2017, Chapter 4: Useful plants – medicines”, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, 2017.

EA Dauncey et al., “Common mistakes when using plant names and how to avoid them”, European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 2016.

S Tranchard, “Revised IDMP standards to improve description of medicinal products worldwide”, International Organization for Standardization, 2017.

Despite focusing on different species, human and veterinary pharmacovigilance share many goals and approaches, offering opportunities for mutual enhancement of the two disciplines.

06 November 2025

Safety systems do not need to be complex to be effective. Shanthi Pal explains the thinking behind the Global Smart Pharmacovigilance Strategy, and how it can be implemented.

17 December 2025

Counterfeit drugs threaten millions worldwide, yet healthcare workers often lack training to spot fakes or report them, leaving this problem largely invisible.

01 October 2025