Ali Azeez Al-Jumaili

University of Baghdad College of Pharmacy, Iraq

The University of Iowa College of Pharmacy, USA

Illustration: iStock (modified)

A recent study puts the spotlight on the extent of substandard and falsified medicines in Iraq, the reasons behind the problem, and the steps needed to address it.

The problem of substandard and falsified medicines impacts the whole world; however, low- and middle-income countries are the most affected. Iraq is one such middle-income country with its share of SF medications.

A 2019 Iraqi Ministry of Health (MOH) report found that around 60-70% of medicines in the private sector do not enter the country through official processes (they are neither registered nor quality tested) – a problem that arose in Iraq after 2003, when the importation of medicines to the private sector became decentralised. Substandard and falsified (SF)medications are usually available only in the private sector, as public sector procurement is secured by a state company called KIMADIA, a directorate in the Iraqi MOH.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition, pharmacovigilance encompasses adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and all other drug-related problems, including SF medications. Therefore, the Iraqi Pharmacovigilance Centre (IqPhvC), which is part of the Iraqi MOH, plays a vital role in collection, analysis, and risk minimisation measures related to SF medications. Its SF-related activities include enhancing healthcare provider awareness, promoting detection, reporting, and distributing alerts. In that role, IqPhvC receives notifications, reports, and letters from different sources, such as the marketing authorisation holder (MAH) or its representative in Iraq, healthcare providers (including pharmacists), consumers, or any other body.

Upon receiving a report about an SF medicine, the IqPhvC checks the product’s registration status, the availability of an importation certificate, and the national laboratory certificate of analysis. The centre then develops an alert, requesting the Iraqi Pharmacists Syndicate (IPS) to distribute it to the community pharmacists by posting it on their official website and Facebook page. Additionally, The IqPhvC informs the Inspection Directorate to start their investigations around the products in question.

When there is a claim or evidence of a quality, safety, or effectiveness problem, the IqPhvc, in collaboration with the Inspection Directorate, has the authority to recall, suspend, and withdraw medicines. As disciplinary actions, the Inspection Directorate can confiscate and destroy SF medications. It is worth noting that neither the MOH nor the private sector has an electronic tracking system to detect the locations of SF medications inside the country. Therefore, the only way to identify SF medications involves the MOH inspector visiting drug stores and community pharmacies and investigating reports from pharmaceutical company representatives, healthcare providers, or other notifiers.

In a collaboration between faculty and a postgraduate student at the University of Baghdad College of Pharmacy and IqPhvC, we published a recent study to evaluate the experience of Iraqi pharmacists and pharmaceutical companies’ representatives with SF medicines, which identified the reasons behind and a suggested solution to this multifaceted epidemic. Additionally, our study evaluated the national pharmacovigilance alerts about SF medications and pharmacists’ abilities to detect and report SF medications. The study drew on three sources of information: the IqPhvC alerts of SF medicines, interviews with international pharmaceutical companies’ representatives, and a survey for community pharmacists.

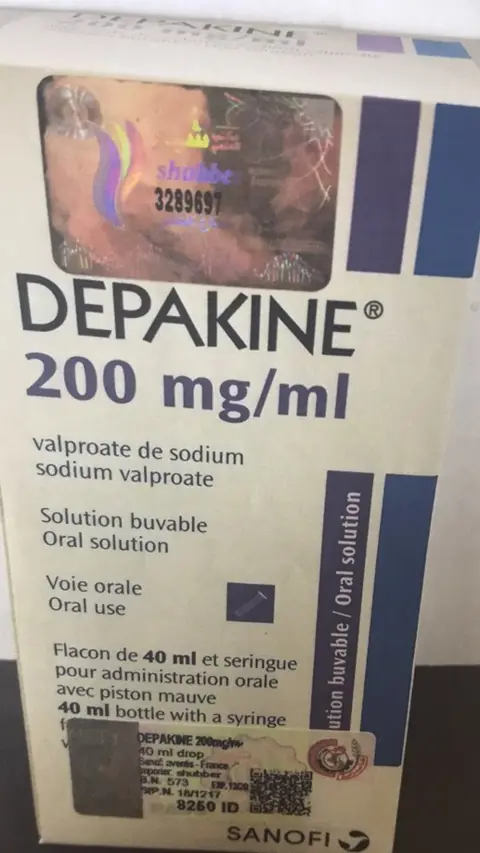

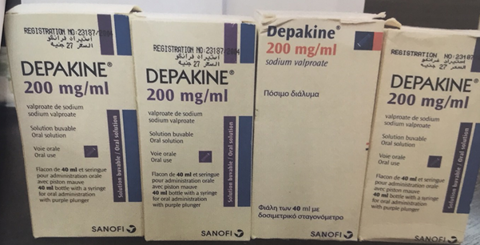

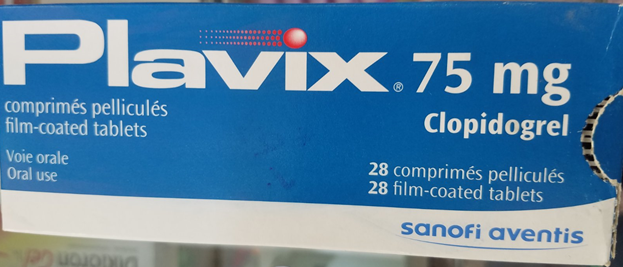

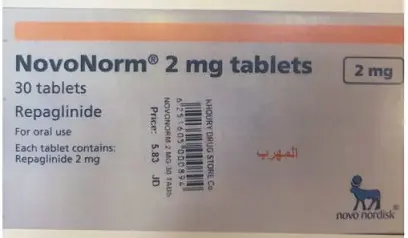

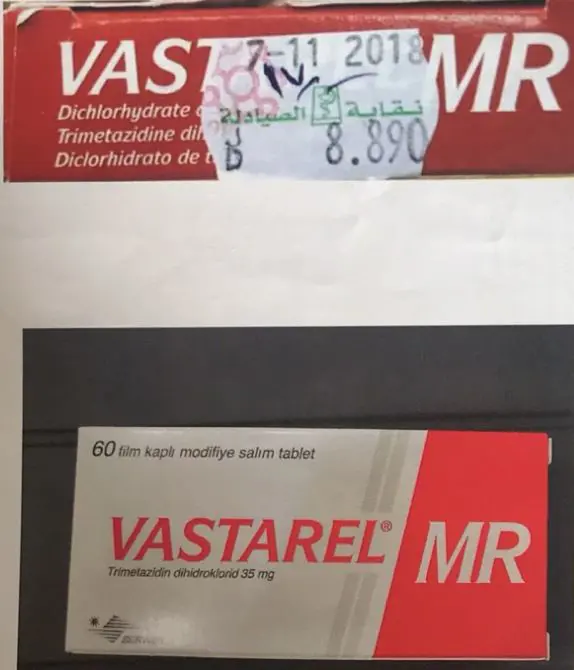

Our study found that the IqPhvc received 183 reports related to SF medications from the representatives of 25 international companies over the past five years (2016-2020). The majority of the reports were about substandard (parallel) medicines, and only 29 (15.8%) of the reports were about falsified medications. The study included interviews with 12 pharmacists representing eight international pharmaceutical companies in Iraq and surveys of 590 pharmacists. More than half of participating pharmacists (59.4%) were able to identify SF medications quickly from their packages. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, only 25.6% of pharmacists were willing to report those SF medications to the IqPhvC.

The participants in the survey and interviews agreed on common causes of SF medications: low prices and higher profitability of SF medications, non-sustainable availability of registered medications, lengthy process of the legal medicine approval route and registration, inadequate border security measures, and inadequate awareness among healthcare providers and the public of SF medications. They also agreed that IqPhvc national alerts of SF medications and the IPS’s price stickers are helpful to identify SF medications. Furthermore, the study highlights a need to implement a track and trace system to detect SF medicines in the supply chain. So far, unfortunately, there are no curative correction measures to address the problem of the SF medicine in the Iraqi private sector.

In summary, the SF medication problem in the Iraqi private sector is multifaceted and requires effective collaboration between different entities, including health officials, border agencies, Iraqi Pharmacists Syndicate, healthcare providers, and registered pharmaceutical companies. While some of those collaborations have begun – in particular, between IqPhvC and other health official entities and pharmaceutical companies – there is still considerable work to be done to choke off the supply of SF medications in Iraq.

Read more:

A A Al-Jumaili, Iraq Pharmaceutical Country Profile 2020.

M H Alwan, Health Situation in Iraq: Challenges and Priorities for Action, Iraqi Ministry of Health, 2019.

The annual #MedSafetyWeek campaign reminds us that medicines work best when they're safe. In Aligarh, healthcare workers came together to make that message a living reality.

19 November 2025

Two-thirds of pharmacists in Nigeria witness weekly cough syrup abuse, yet poor reporting systems and unclear guidelines prevent effective intervention, leaving its youth at risk.

03 December 2025

Since 2020, the ICPV has worked to improve drug safety reporting at Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez, with promising outcomes.

16 October 2025