Elena Rocca

@Cause_Health

Associate Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway

Photo: iStock (modified)

Emerging ideas in the philosophy of science challenge a rigid reliance on evidence-based medicine, offering a more nuanced understanding of causal dispositions and patient safety.

What are causes and how can we find them? What’s the value of outliers and unexpected observations for scientific enquiry of causes and effects? How do scientific discoveries happen? And how do social structures and communities help or hinder the process of discovery? Most practitioners would agree that these questions lie at the very core of pharmacovigilance and patient safety. And the same questions are continuously discussed by philosophers of science. Unfortunately, however, there is not much dialogue or exchange across these two disciplines.

Our project, "CauseHealth Risk and Safety: Causation, Probability and Complexity in Pharmacovigilance", exists to develop that dialogue.

CauseHealth works at the interface between philosophy of science and patient safety. Our aim is to contribute to a more self-reflexive and self-critical practice of pharmacovigilance and medicine, but at the same time to get philosophy of science closer to the specific day-to-day challenges of improving patient safety.

Bridging two disciplines – one applied and one conceptual – is a challenge, even when they are grappling with many of the same issues. Embracing such challenge, however, has led us to new and exciting perspectives… and further challenges.

“Each of us has a unique set of dispositions, which affect the way we react to medicines. The challenge is not only to look at what happens at the population level, but to identify the critical factors that determine when and how a medicine can be used safely by a particular individual”

In medical science, there is a general resistance against taking action or expanding knowledge based on evidence that does not include statistical correlations in a reasonably large and reasonably representative sample of the population. After all, the thinking goes, to be based on scientific evidence means to be backed by observation. The question is: what kind of observation?

The current evidence-based paradigm has a clear and exclusive answer to this question: the best evidence of causality comes from controlled clinical trials, and the "second best" from controlled observational studies. However, a global movement of philosophers of medicine is emerging in opposition to that paradigm. Although starting from slightly different conceptual foundations, these scholars have independently reached the common conclusion that, for the purpose of making causal claims in medicine, evidence from causal mechanisms and patient-produced evidence are at least as important as evidence from population trials.

An early CauseHealth initiative was an open letter, published in the BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine journal, in which 42 clinicians and philosophers jointly urged that “statistical approaches, in particular randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews, cannot uncover all causally relevant information, contrary to their widespread assumed status as the universal gold standards of [evidence-based medicine] EBM”.

For pharmacovigilance, this means that hypotheses of harm can be considered as scientifically justifiable and, therefore, worth pursuing even if they are not backed by big numbers and repeated observations. Reports of a specific symptom for a certain medicine might be few – there may be only one – but if they are qualitatively rich and point to a hypothesis for the underlying mechanism, they should be taken seriously. Further work on this front was done in a meeting in Erice, Italy, where 18 experts from different medical fields, together with philosophers and patients, met to discuss the challenge of using patient experiences to improve causal understanding in medicine. A forthcoming report of the meeting, the “Erice Call for Change”, will be soon available as an open access article in the journal Drug Safety.

“Pharmacovigilance is an explorative enterprise, and it is sometimes compared to serendipity: untargeted effects of drugs are first observed when one is not looking for them”

Sometimes we observe that an intervention tends to make a difference in a regular way. For instance, buprofen causes gastrointestinal symptoms in many patients. This observation is useful, because it points to an intrinsic property of ibuprofen. Intrinsic properties, which philosophers sometimes call dispositions, or capacities, or causal powers, are what pharmacovigilance (and medicine in general) is after. We see correlations all the time, but not all of them point to intrinsic properties. From correlations alone, then, it is hard to derive intrinsic dispositions. Paracetamol is correlated with childhood asthma, for instance, but is it because the drug has an intrinsic disposition to cause asthma? Or do asthma and paracetamol use have a common cause, for instance chronic airway infections?

From such simple examples, the connection between the practice of pharmacovigilance and the philosophy of causal dispositions seems almost trivial. Clearly, hypotheses of harm must be hypotheses of intrinsic dispositions, and must be evidenced accordingly. This is, however, not so simple.

In fact, harm detection is increasingly based on the recording of external relations rather than intrinsic dispositions. Causes and effects are mainly searched for as factors that correlate in populations. In our project, we have seen this by examining risk assessment methodologies in general. We also specifically analysed different approaches to evaluate the toxicity of petroleum residues in the environment. From this work, we have seen that thinking dispositionally requires a much more holistic, or ecological approach, than the traditional procedures for risk assessment allow. Pharmacovigilance, as a type of risk assessment, is no exception.

There is, however, another point to make: looking for causal dispositions is demanding. It brings us into the uncertain territory of mechanistic knowledge, and at the same time, it demands that we understand not only one phenomenon, but also its broader context. This is not always possible. Moreover, while all methods are useful to evidence causal dispositions, none of them is perfect. We can see a correlation, but we will never be able to "see" a disposition: we can only collect some symptoms of it.

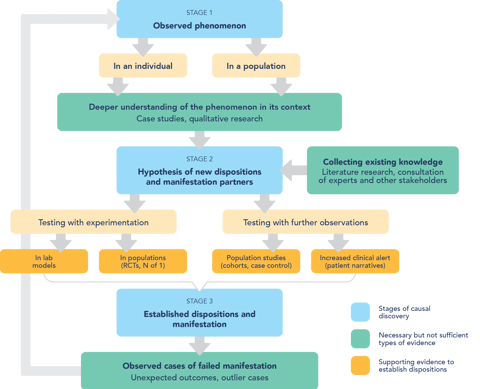

For medicine and pharmacovigilance, this means that causality assessment is a complex effort, which needs a plurality of evidence. How, however, should such causal evidence be evaluated for the purpose of looking for a causal disposition of a drug to harm a certain patient? What counts more?

In our recent article, “Causal Evidence and Dispositions in Medicine and Public Health”, we consider systematically the different methods used in medicine as evidence of causality. All have advantages and disadvantages for the purpose of evidencing causal dispositions, which we describe. Ultimately, we propose the approach that we consider to be the best, if we want to have good evidence of causal dispositions.

This work applies to medicine and public health in general, and we are now in the process of working out what a dispositional approach to pharmacovigilance would look like.

Pharmacovigilance is an explorative enterprise, and it is sometimes compared to serendipity: untargeted effects of drugs are first observed when one is not looking for them. As is the case with serendipity, for harm detection one also needs chance and a prepared mind (the clinician’s or the causality assessor’s). But does that mean that in order to improve pharmacovigilance we must promote discoveries by chance? How can this possibly be done?

For an answer, we started by looking at how serendipitous discoveries happen, and how they can be promoted. The latest developments in philosophy of science point out that serendipity in science needs "chance" and "a prepared mind", but not only those things. It needs also a responsive network of scientists and stakeholders, able to take up the unexpected observations and make use of them. We argue that isolated measures within the narrow boundaries of pharmacovigilance can be useful, but not sufficient, to improve the detection of the unexpected. More groundwork at the very structure of the medical community is still needed to create a flexible trans-disciplinary network in pharmacovigilance.

According to our reasoning, there is a need for institutional changes in medical training and research, so that clinicians, decision makers, causality assessors, patients, and manufacturers can create a common culture and be critical of their own premises and assumptions. Building on this work, CauseHealth Risk and Safety will continue using a dispositional understanding of causality and a transdisciplinary approach to advance pharmacovigilance and patient safety.

Pharmacovigilance is an explorative science which starts by detecting unexpected and significant observations. To promote such serendipitous observations, it is not sufficient to make changes within the narrow boundaries of pharmacovigilance. Instead, the whole medical community must make an effort to promote trans-disciplinary approaches to medical enquiry. Here are some summarised examples of the changes we suggest:

The CauseHealth: Risk and Safety core research team consists of Ralph Edwards, Marie Lindquist, Rani Lill Anjum and Elena Rocca. The project is a research collaboration between UMC and the Centre for Applied Philosophy of Science at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU).

UPDATE: Since we published this article, the CauseHealth team has released a new book, Rethinking Causality, Complexity, and Evidence for the Unique Patient, edited by CauseHealth principal researchers, Rani Lill Anjum and Elena Rocca and Samantha Copeland, Delft University of Technology. The book is published as open access, available for free download here.

Listen to this article as an episode of the Drug Safety Matters podcast.

MUEs are typically used to improve the safety of drugs, however, may they also have a role in measuring the adherence to risk minimisation measures?

06 August 2025

Spontaneous adverse event reports pose significant challenges to pharmacovigilance scientists. How may we turn them into opportunities that benefit our pharmacovigilance systems?

04 June 2025

Online psychedelic forums hold untapped safety data. AI analysis of user narratives could help pharmacovigilance systems detect risks missed by traditional reporting.

13 November 2025