Gerard Ross

Head of Global Communications, UMC

Image: multiple, including Noah Boyer, Unsplash (modified)

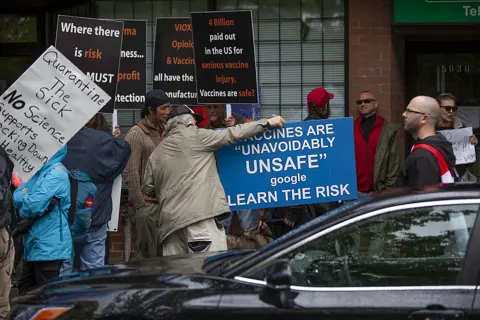

Understanding the difference between anti-vaccination belief and vaccine hesitancy is key to setting public health communication strategies, and the stakes have never been higher.

For many countries battling the current COVID-19 pandemic, supply of vaccines is the major hurdle to be cleared before societies and economies can fully re-open. But for other countries, where vaccination programmes are already well advanced, the emerging problems have shifted to the demand side of the equation. Fuelled by anti-vaccine disinformation and an array of other cultural and economic factors, vaccine hesitancy looms as one of the primary global health communication challenges of the coming years. Getting vaccine communication right will be a key ingredient to boosting vaccination rates to a point where the world can return to some sort of normal.

While there are obvious overlaps between the anti-vaccine movement and vaccine hesitant people, they are very different groups and the strategies for dealing with them need to be informed by an understanding of their differences.

“The terms anti-vaccine or anti-vaccination usually refer to those who express ardent vaccine denial and an outright refusal to be vaccinated,” says Dr Tom Aechtner, a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Queensland in Australia.

“It refers to the active rejection of scientific consensus on vaccines. And what's key is that this idea of anti-vaccination doesn't suitably describe a lot of people who might simply have questions or worries about vaccines.”

“This idea of anti-vaccination doesn't suitably describe a lot of people who might simply have questions or worries about vaccines”

The questions and concerns of the vaccine hesitant, he explains, are wide ranging and can include misunderstandings about what ingredients are in vaccines, reservations about how many vaccines someone should receive in any given period, or concerns about whether vaccines could harm their children. Also, in the current context, many people who are otherwise pro-vaccine, express concern that the new COVID-19 vaccines were developed too quickly or rely on untested technologies – fears that, while ill-informed, are understandable. And beyond those concerns, there are many others for whom the perceived benefits of receiving a vaccine are outweighed by the logistical or financial impediments to getting a shot.

“Vaccine hesitancy is much broader than the classification of anti-vaccine,” Aechtner says. “Research has also found that around the world, the percentage of people who might be truly anti-vaccine is actually quite small, around 2 to 3%. But a much larger proportion of the population express vaccine hesitancy – anywhere from 20 to 40%.”

This distinction has profound implications for public health communication strategies.

The anti-vaccination movement is almost as old as vaccines themselves – indeed there was prominent, organised opposition to the very first cow pox inoculations. And counter intuitive as it may seem, a lack of information is not necessarily the problem. In fact, explains Aechtner, antivaxxers often have deep knowledge about the science and practice of vaccination, and they are often armed with considerable information about perceived harms that people believe were inflicted by vaccines. But as they filter information through their own cognitive biases, their conclusions fall outside the scientific consensus. Motivated then by distrust in government or pharmaceutical companies, sociocultural values including anti-establishment sentiment – among other drivers – the impact of anti-vaccination voices often far exceeds their numbers.

From a purely public-health standpoint, lack of vaccination among the few true anti-vax proponents is not, in itself, a major concern. But it’s the disproportionate effect their messaging has on the vaccine hesitant that can pose a significant threat. The question, then, is how to defuse that messaging.

“Expending your energies to reach people who are committed anti-vaccinators is unlikely to have much benefit”

While the temptation for the scientifically minded is to confront the anti-vaxxers head-on and dismantle their arguments with facts, Aechtner warns that the evidence runs against this approach, and that directing appropriate communication efforts at the vaccine hesitant receivers of misinformation is more effective than attacking the vaccine denying senders.

“Researchers have concluded that health communicators should actually avoid trying to convert antivaxxers or ardent vaccine deniers. That's because fervent anti-vaccinators are really the least open to impartial argumentation, scientific evidence, and discussion,” Aechtner says.

“Expending your energies to reach people who are committed anti-vaccinators is unlikely to have much benefit. Instead, health communicators should really be more concerned with trying to reach what we call the fence-sitters; people who are vaccine hesitant but still undecided. They represent a much larger segment of the population, and they are likely to still be open to some discussions.”

The fence-sitters, he says, may have been exposed to vaccine misinformation or disinformation, and may even have strong opinions, but that have not yet made the leap to identifying as anti-vaccine. The research on how to reach fence-sitters suggests that success comes, not from lecturing them or telling them they are wrong, Aechtner says, but rather “finding their desires, identifying their values, and leading them to a solution that works for what they want, which is, in most cases, the safety of their children” or some other rational goal.

“Misinformation isn’t bound to scientific facts. It can be sensational, and misinformation tends to spread and be sticky.”

Key to achieving that success, therefore, comes from understanding the vaccine hesitant and the communities to which they belong, and speaking in a language that is understandable to them. In practice, the lesson for health communicators is that scientific knowledge and evidence-based arguments frequently need to take a back seat to cultural sensitivity and emotional intelligence.

While there will always remain a need to build a foundation of accurate, factual information and resources for those genuinely searching for answers, the work of turning around the vaccine hesitant relies heavily on persuasive cues and emotional appeals – the very techniques that anti-vaxxers deploy so successfully. While Aechtner concedes this can be uncomfortable for medical and academic practitioners, he argues that the rhetorical tools themselves are value-neutral and that it is ethical to deploy them honestly within a factual framework.

Even so, pro-vaccine communicators remain at a disadvantage to the anti-vaxxers in the battle to win over the hesitant.

“Misinformation isn’t bound to scientific facts,” says Aechtner. “It can be sensational, and misinformation tends to spread and be sticky.”

Vaccine misinformation and disinformation also taps into a deeper history and language of other fringe beliefs.

“It’s amazing how so much of it goes back to the small group of tropes that crop up in conspiracy theories of all types,” Aechtner says. “In the end, much of it boils down to narratives of distrust. We just can’t trust who’s in charge.”

“And there’s good reason why people have that distrust. We have been let down by government, by pharmaceutical companies and industry. So, it plays upon a kernel of truth and the pre-existing distrust makes these messages so sticky.”

In the past, traditional media gatekeepers had more power in setting the agenda for public discussion, and it was harder for fringe views to reach a mass audience. But social media changes that balance.

“In theory, social media can certainly be a powerful tool for pro-vaccine, pro-science messages,” Aechtner says. Unfortunately, the algorithms of many social media platforms reward engagement, which too often simply means conflict. This is another reason why arguing with antivaxxers online is a bad idea – fighting them sometimes adds fuel to the conflict, and disagreements may spread the misinformation more widely.

“The research has found that misinformation is re-shared more frequently in social media than actual data. And researchers have also found that people who get their news primarily from social media sources tend to be more likely to be exposed to and believe the misinformation they hear.”

If all these pro-vaccination communication challenges feel insurmountable, there is help at hand in the form of a growing body of research and evidence-based resources. The World Health Organization is a good starting point both in terms of vaccines in general and COVID-19 vaccines in particular. For his part, Aechtner, who holds a research fellowship examining how to improve vaccination rates in Australia, has also launched an open online course to help people understand vaccine hesitancy and respond to anti-vaccination claims. The course, Antivaccination and Vaccine Hesitancy AVAXX101, is hosted by The University of Queensland through the edX platform and is available to people anywhere in the world.

Interest in the course is encouraging. Aechtner explains that enrolments so far include more than 1200 people from around 80 countries, representing many occupations such as journalists, science communicators, educators, and public health workers.

The diversity of participants is important. With trust and community being such powerful factors in determining the impact of information, it’s important that pro-vaccine messaging is not all coming from establishment voices. In this context, Aechtner points to pharmacists and nurses as under-utilised resources in health communication. Research shows they are highly respected, credible professions, whose members work closely with patients, often as sounding boards for patients seeking more information than they feel able to seek from their doctors.

Pharmacists, in particular, are especially experienced in speaking to patients about medications in general. Now, as more pharmacists are becoming involved in administering vaccinations themselves, the seeds of trust they have sown within the community can be valuable in bringing fence-sitters down on the side of vaccines.

The persistence of real antivaxxers and the stickiness of their disinformation will likely always be with us. As frustrating as that can be, the research on vaccine hesitancy provides a sense of perspective on how limited they are in number, allowing health communicators – and indeed anyone who trusts science and evidence – to counter dangerous myths and reduce hesitancy with empathy, honesty, and understanding.

Oman’s VigiMobile launch is more than a technical upgrade. It signals a strong commitment to patient safety and public participation in pharmacovigilance.

17 September 2025

How can we make healthcare safer for children? ISoP’s Angela Caro-Rojas shares insights ahead of World Patient Safety Day.

04 September 2025

Prof. Singhal passed away on 19 April 2025. He is survived by his wife, children, and a large community of pharmacology researchers who had the privilege of training under him.

02 July 2025