It’s symptomatic of the times that Marie Lindquist hasn’t set foot in UMC’s offices since March. She’s looking sharp and suitably autumnal in a pair of (what else?) signal red trousers and matching jumper layered over a crisp white blouse as she takes her seat in a meeting room that could comfortably seat eight for an appropriately socially distant interview. Her breezy manner is at odds with the mood on the streets outside, which remain bare at lunchtime on a workaday Tuesday despite the sun and blue skies. Inside, an office whose staff has doubled in the 10 years since she became director is strangely quiet. Deceptively so.

"I have always felt very strongly that what I do is about people. Looking back, I think that’s been my strength – that I’ve always seen the patient behind the data"

With the world still holding its breath in the hopes of a “cure” for the pandemic, months – if not years – of preparation are about to be put to the test. Work has already begun monitoring the safety of medicines being used to treat coronavirus and those efforts are set to enter a second, more intensive phase should any successful vaccine candidates emerge.

It is precisely the kind of situation for which the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring – and by extension UMC – was brought into being. In the 1960s, the thalidomide crisis showed the need to have systems in place to protect patients from harm with the tragic realisation that although medicines do a lot of good, they can also cause serious injury or even death.

“Everyone’s desperate to get a vaccine out and the hope then is that lots of people will get it, but that also means a lot of people will be exposed to something new and we need to monitor its safety and effectiveness,” Lindquist says. “Because even if there’s a very rare adverse reaction – say 1 case in 10,000 – if you have 10, 20, or 100 million people getting vaccinated, many of them could be harmed if we don’t detect the first sign of a problem swiftly.”

As she prepares to pass the baton to her successor, Hervé Le Louët, Lindquist is confident that the organisation she has dedicated her working life to is more than up to the task. From its original role as custodian of VigiBase, WHO’s database of individual case safety reports – the world’s largest repository of reported adverse drug reactions – UMC has grown under her leadership into a sustainable, financially viable enterprise, built on solid scientific foundations. She could give the standard business metrics to make that case, but her preferred measure of success is that she has maintained the integrity and soul of an organisation that has patients’ best interests at heart and where people come to do good.

“We have been an important voice in putting pharmacovigilance on the map and making sure that it is recognised as an essential part of healthcare in every country,” she says.

Lindquist also takes pride in the knowledge that UMC has continued to set the scientific agenda for pharmacovigilance with its groundbreaking methods and tools.

“We were the first to introduce a routine data mining approach to screening big data for safety signals in the 1990s. What was initially regarded with some level of suspicion is now mainstream practice,” she says.

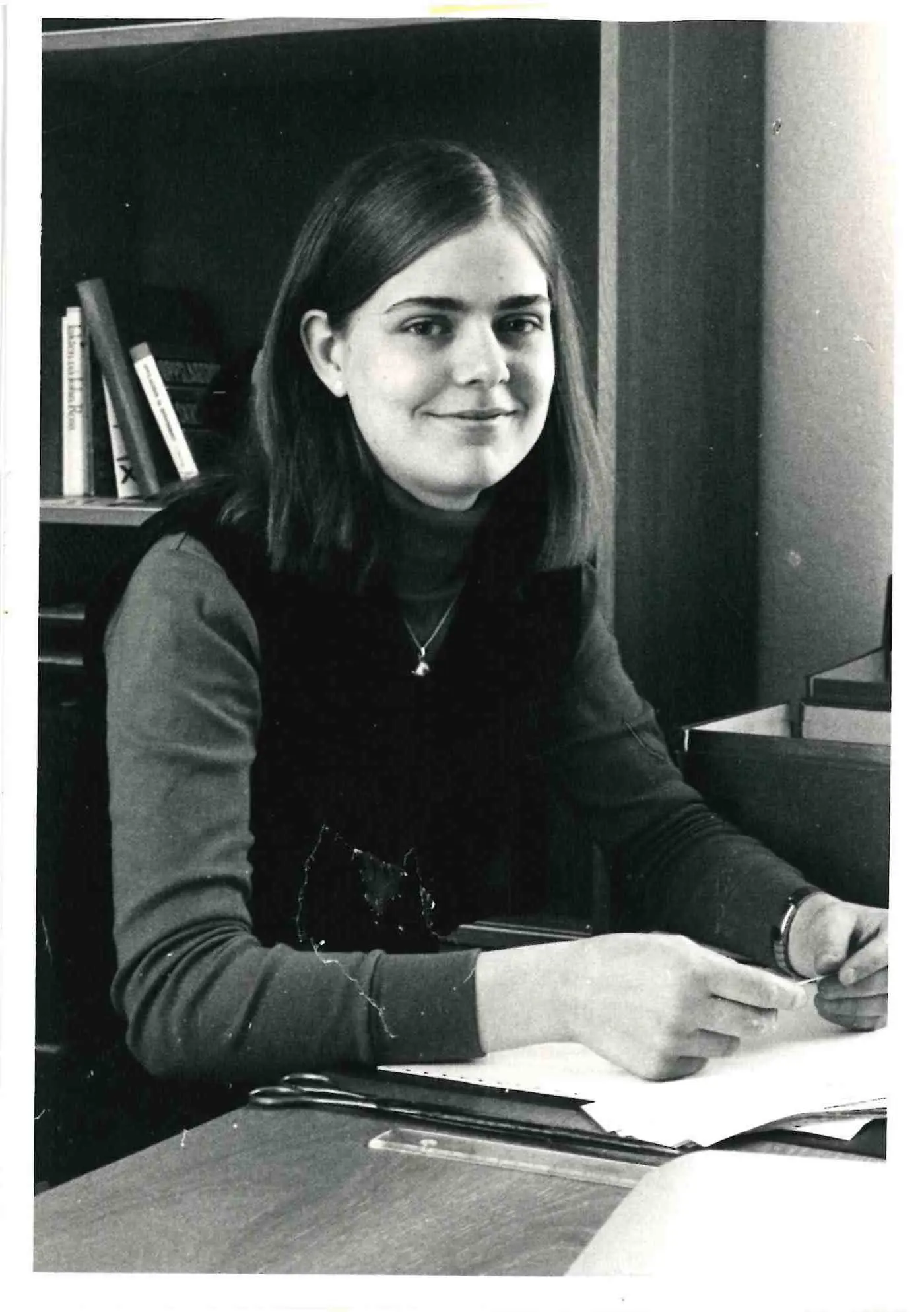

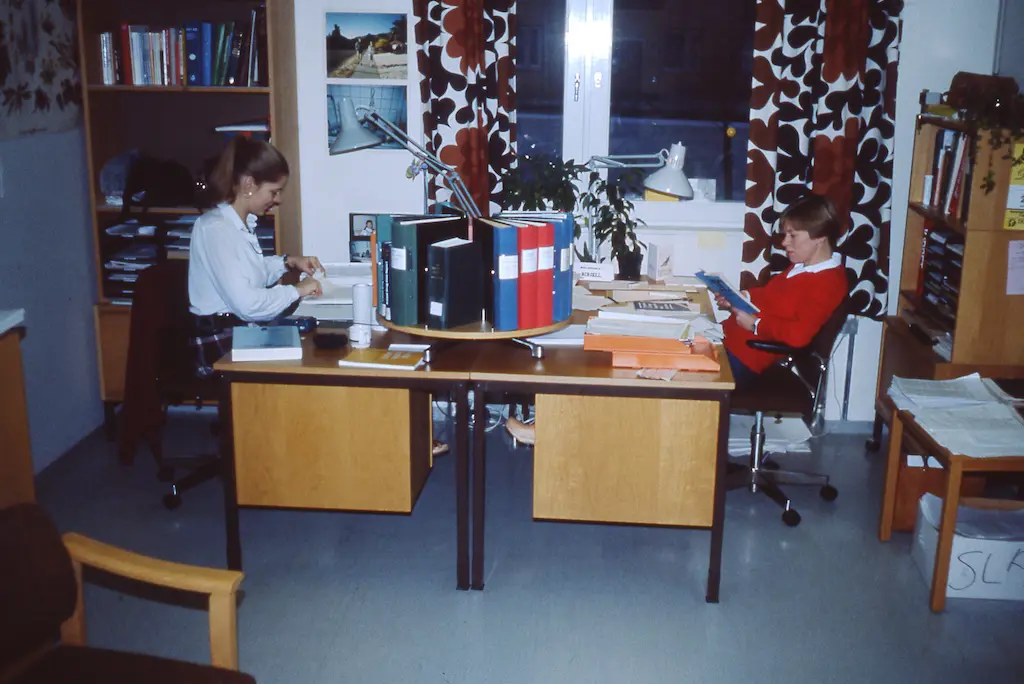

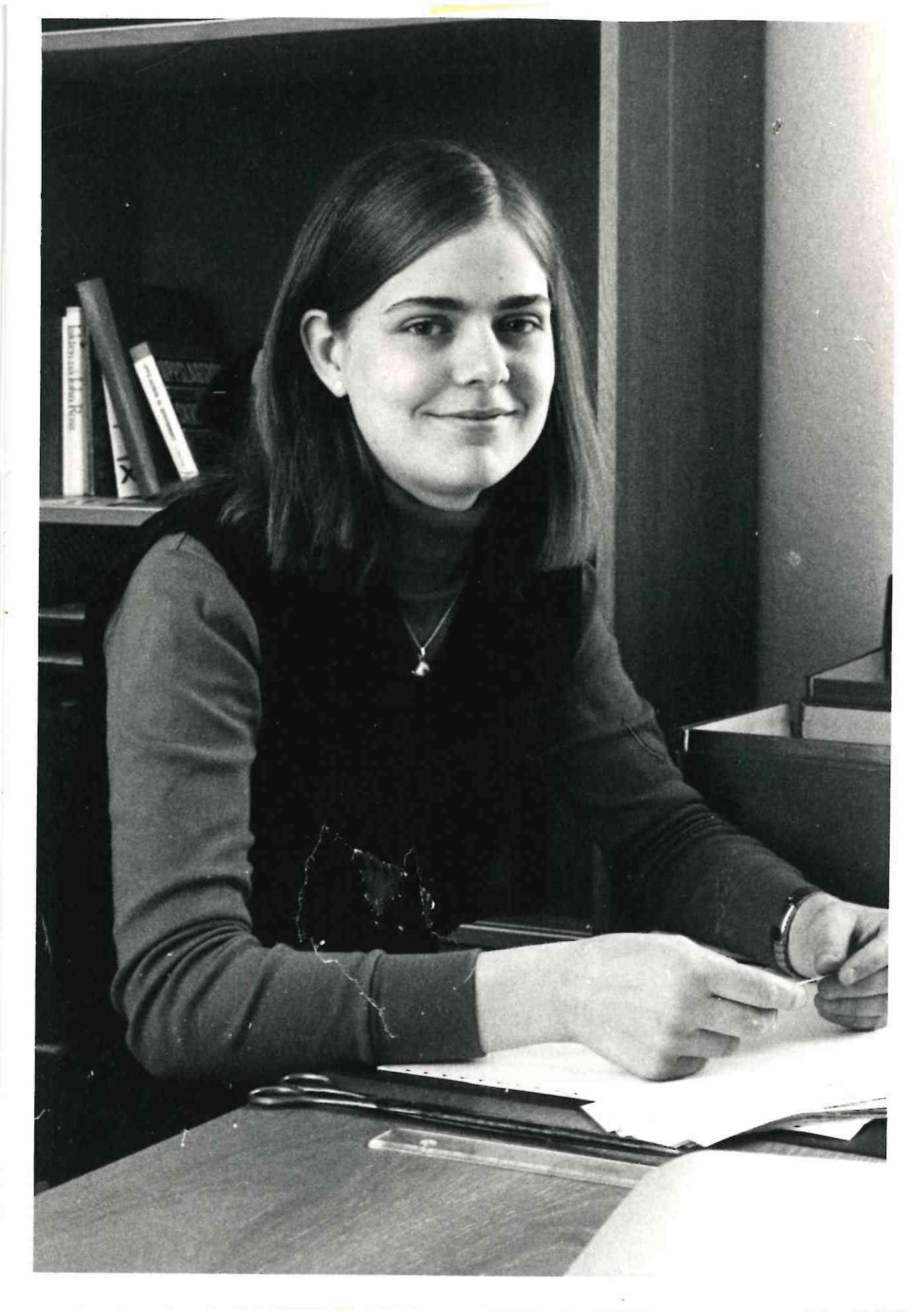

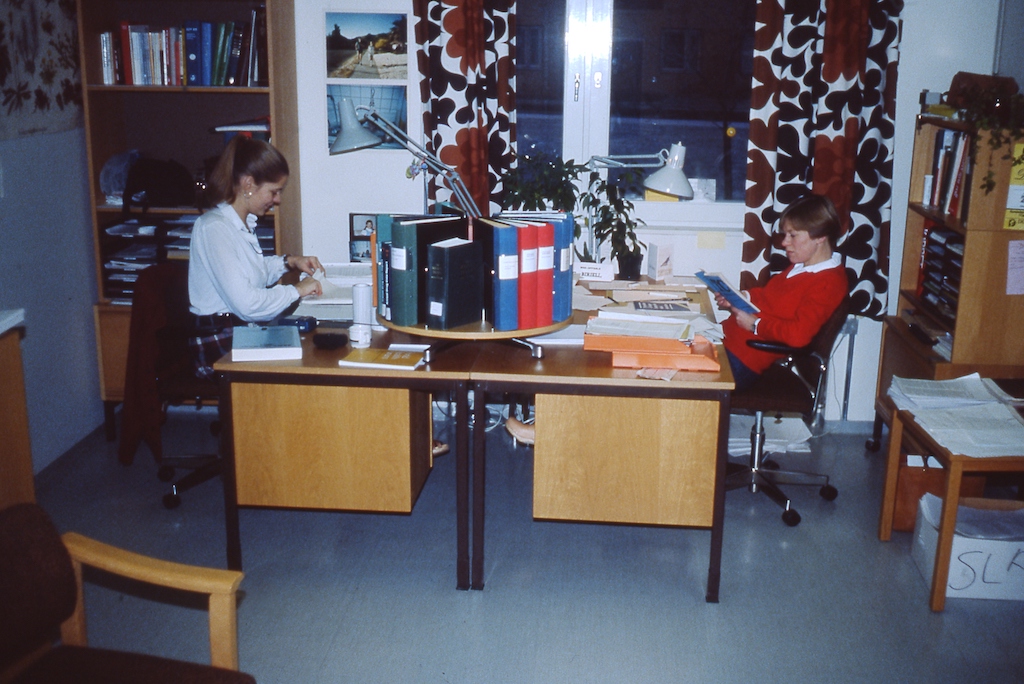

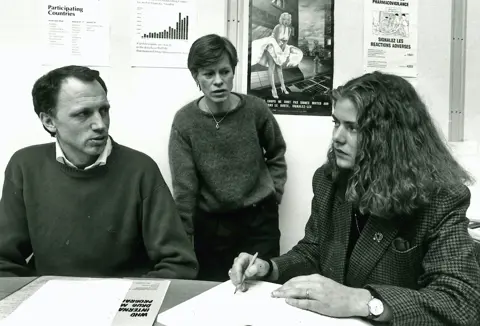

When Lindquist joined UMC in 1979, it was still finding its feet – much like the newly graduated pharmacist from Uppsala University. She had spent a few months at the Medical Products Agency, which was in the same building, and by chance saw on the notice board that the WHO Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring was looking for a pharmacist. She had already decided she didn’t want to work in a pharmacy as she thought that would be boring. And she wanted something international because she had always liked languages and the idea of the world being a little bit bigger than Sweden.

“I knocked on the door and Sten [Olsson] was there. I said I could start tomorrow, and he said, OK. That was my job interview,” she laughs.

Lindquist admits “it wasn’t exactly part of a considered career plan”. She had studied to become a pharmacist because she was interested in medicine but didn’t like the idea of cutting into people. At UMC, though, she found a calling and a sense of duty to the cause that has stayed with her.

From the beginning there was a lot of effort put into doing the job, collecting the data, analysing it, producing signals. She started off with data entry, taking care of incoming reports and coding each medicine to make it searchable – this would later provide the structure for the WHODrug dictionary, UMC’s main source of income. “The reports of suspected adverse reactions were still coming in on paper then. Making all the corrections manually could have been tedious,” she says. “But I read the case information and saw a person. I don’t work in healthcare as such, I don’t sit by a patient’s bed, I’m not doing acute surgery, but I have always felt very strongly that what I do is about people. Looking back, I think that’s been my strength – that I’ve always seen the patient behind the data.”

UMC has continued to develop ever more sophisticated ways to structure data and detect signals. “It simply isn’t good enough to say we are going to look for the usual reactions, because our job is to find the unknown,” says Lindquist, who had a hand early on in developing analytical systems and search strategies to extract the information from the database and put it together. “But recognising that a medicine may cause harm in some patients doesn’t really lead anywhere unless the knowledge is made available to those who need it, in a way that actually improves the lives of patients.”

As one of the architects of the original Erice Declaration, which laid the groundwork for the development of good communication practices in pharmacovigilance, Lindquist has been a leading advocate for more patient-centred communication throughout her directorship. It is also something she would like to write about now that she will have the time.

“You have the public health perspective of medicines and how they are used and then you have the individual’s perspective. Everyone talks about being patient focused, but I’m not sure we really are,” she says. “There’s a lot more to be done in actually making sure that what we do in pharmacovigilance benefits individuals. What do people want from us? What do they expect? What do they need? How can we do better?”

To give just one example she cites patient reporting where although everyone agrees that patients need to report and that it’s important to hear their stories, it’s rarely that simple.

“In many countries it’s possible for patients to report ADRs to their national pharmacovigilance centre, but how do they know where to report and how to report? How many people know there is a regulatory authority responsible for reporting side effects? Do they know the name of the regulatory authority? So, first you have to find out that there is a regulatory authority that you can report to. Then you have to find their website. You have to find that information on their website. Few make it easy.”

Free of political or commercial considerations – although UMC works closely with WHO it is organisationally and financially independent – UMC has been able to push its scientific agenda, always with the patient in mind. Not one afraid to ruffle a few feathers, Lindquist has fought that battle in her own way. “I’m a great believer in integrity and standing up and being counted. If it’s something we ought to do, we should do it.” But she also believes in the need for diplomacy and constructive dialogue. Instead of seeing compromise as something negative, she thinks of it as a positive step in the right direction. She was pleased to hear her successor referring to his new role of CEO as that of a “pharmacodiplomat” (“his word; I wish I’d thought of it”) determined to put the patient front and centre.

“He has the right feeling for UMC. He really wants to work with us. He thinks of UMC as his dream job and that’s a very good start,” she says.