Linda Härmark

Deputy director at the Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb.

With the PAVIA project ending, participants identified what makes for a thriving pharmacovigilance system in countries burdened by poverty related diseases.

Poverty related diseases (PRDs) still affect large parts of the population in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) necessitating the development of new and improved medicines and vaccines to fight these diseases. However, they are being used by patients based on limited information about their safety. Since many of the new medicines and vaccines preventing or treating PRDs will be deployed mainly in LMICs, it is important that these countries develop robust pharmacovigilance systems to monitor their safety.

PhArmacoVIgilance Africa (PAVIA) was a five-year project that sought to strengthen the national pharmacovigilance systems in Eswatini, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Tanzania. The PAVIA project aimed to improve both the National Medicines Regulatory Authorities’ (NMRA) capacity to conduct pharmacovigilance, and to strengthen collaboration with Public Health Programmes (PHPs) with a focus on the National Tuberculosis Programme (NTP) for reporting, sharing and analysing safety data on MDR-TB medicines. The project aimed to use the NTP as a model for similar collaborations with other PHPs. The collaborations were arranged in triangles, connecting the local partners (amongst which the NMRA, NTP and Medical Research Institutes). One of the deliverables of this project was a blueprint for strengthening pharmacovigilance systems in resource limited countries. In the blueprint, lessons and best practices from the project are illustrated using examples from the four PAVIA countries. This article highlights a few of these examples.

“After observing the problems with reporting, the national tuberculosis program has introduced a tracker for case-based reporting. We customised DHIS2 and we have implemented it in all our centres now; that is helping us. We included a link to report adverse events and to see laboratory results.” [...] “We are working to install an immediate notification system which will notify us when an adverse event is entered from any facility by a healthcare professional. [...] The tracker is better; it reports in detail... The only thing left is sending the adverse events to the EFDA.”

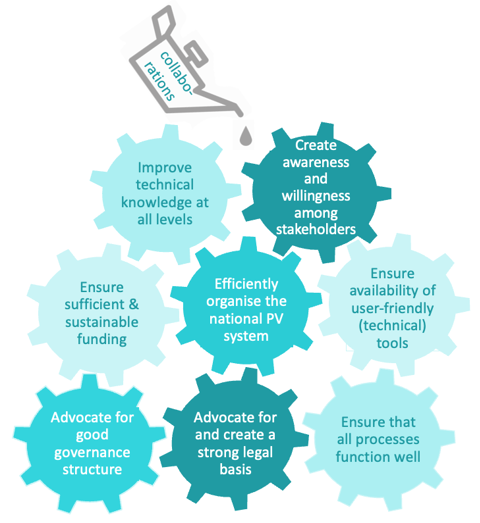

Based on the experiences from the project, a model of the key components for a well-functioning pharmacovigilance system was designed. A national pharmacovigilance system may be regarded as an engine with multiple gears. All gears must be present to keep the machine running. If any of the gears do not function properly, the machine will work less efficiently or may even come to a halt. Strong, effective, and sustainable collaborations are the lubricating oil in this machine. To make the pharmacovigilance system (the ‘engine’) function optimally, some or all elements (the ‘gears’) may have to be improved.

For a pharmacovigilance system to thrive, a dedicated pharmacovigilance policy and set of laws and regulations regarding pharmacovigilance is needed. A national pharmacovigilance system should have a national pharmacovigilance centre to provide a focus for implementation and enforcement of this legislation. Enforcement also requires prioritised sufficient and sustainable funding for pharmacovigilance operations as well as dedicated personnel, and active support from national governments. The PAVIA project worked on strengthening pharmacovigilance policies and funding models in the four participating countries and used the results of the project to develop materials that other countries may use to strengthen their pharmacovigilance systems.

Larger countries will need to have subnational structures in place to bring pharmacovigilance to all levels of the national PHP. Electronic tools, whether domestically developed or sourced internationally, aid in improving ADR reporting (Box 1). Efficient data flows may comprise several options for reporting, including paper forms, mobile phone applications, and web-based reports, while avoiding double reporting. Ideally, pharmacovigilance data should be fed into a single central pharmacovigilance database (Box 2). Dedicated training of healthcare workers and national pharmacovigilance centre staff is critical for a fully functional pharmacovigilance system. Training should be structured to support the system, and should be tailored to the staff’s needs, enabling healthcare workers to identify side effects and report these to the national pharmacovigilance centre and pharmacovigilance staff to learn how to systematically search for signals and act upon them. Blended learning courses can be effective for providing such training (Box 3).

During the PAVIA project, Nigeria’s NAFDAC has made VigiFLow their main database, replacing other local databases. They have also introduced e-reporting and the MedSafety app which directly forwards reports to VigiFlow without manual data-entry. By streamlining their processing and increasing the number of staff able to manage the database, they have removed the backlog of reports which enables real time monitoring of the safety of drugs. The number of reports (80%) sent to the global database at Uppsala Monitoring Centre has also increased.

During the PAVIA project, Nigeria’s NAFDAC has made VigiFLow their main database, replacing other local databases. They have also introduced e-reporting and the MedSafety app which directly forwards reports to VigiFlow without manual data-entry. By streamlining their processing and increasing the number of staff able to manage the database, they have removed the backlog of reports which enables real time monitoring of the safety of drugs. The number of reports (80%) sent to the global database at Uppsala Monitoring Centre has also increased.

Engagement of partners, including the PHPs, universities, medical research institutes, professional organisations, and non-governmental organisations, is critical to strengthening national pharmacovigilance systems. These partners can help to create awareness among medical students, healthcare workers and PHP staff working on specific diseases to increase ADR reporting (Box 4), and support data analysis, reporting, and conducting pharmacovigilance research and training. Finally, they may be able to attract additional funding for special pharmacovigilance related projects or tasks.

By continuously working on improving the different gears in the pharmacovigilance engine, the countries' pharmacovigilance systems will be strengthened, which will ultimately lead to improved patient safety.

“The blended learning training was very effective. We had an in-person introduction. You do the rest of it in your own time. So, if you have something that you do not fully understand, then you have the time to give it more consideration. That was mainly why it was helping. Also, there were offline modules, which is a facilitator. Some people do not have internet so that would be a problem. So ideally you could also download it in the office and work on it at home.”

“The blended learning training was very effective. We had an in-person introduction. You do the rest of it in your own time. So, if you have something that you do not fully understand, then you have the time to give it more consideration. That was mainly why it was helping. Also, there were offline modules, which is a facilitator. Some people do not have internet so that would be a problem. So ideally you could also download it in the office and work on it at home.”

The national pharmacovigilance centres in all the four project countries benefitted from the monitoring and evaluation system introduced by PAVIA. This system included a comprehensive baseline assessment investigating strengths, weakness, opportunities and threats to their national pharmacovigilance system, a roadmap developed by the countries’ national PAVIA triangles led by the NMRAs with specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) objectives to address the weaknesses identified, annual sessions to evaluate how the centres were doing in achieving the set objectives, and an assessment of the state of the national pharmacovigilance system at the end of the project. Maintaining a continuous monitoring and evaluation cycle will enable national pharmacovigilance programmes to continue to improve their effectiveness in identifying and acting on medicine safety issues.

DR-TB focal person: “NTP is just identifying the adverse events from the treatment sites, and then records the events and reports these to the TMDA, which are the ones who are supposed to do the signal detection and causality assessment.” [...] “The TMDA needs to provide feedback, because the policy allows them to do that, and we are supposed to follow their advice regarding the safety of the patient. If there is a need to change the treatment modality or policy, we will do that. But we cannot do that without having evidence or recommendations from the PV unit of the TMDA.”

DR-TB focal person: “NTP is just identifying the adverse events from the treatment sites, and then records the events and reports these to the TMDA, which are the ones who are supposed to do the signal detection and causality assessment.” [...] “The TMDA needs to provide feedback, because the policy allows them to do that, and we are supposed to follow their advice regarding the safety of the patient. If there is a need to change the treatment modality or policy, we will do that. But we cannot do that without having evidence or recommendations from the PV unit of the TMDA.”

Read more:

The annual #MedSafetyWeek campaign reminds us that medicines work best when they're safe. In Aligarh, healthcare workers came together to make that message a living reality.

19 November 2025

Two-thirds of pharmacists in Nigeria witness weekly cough syrup abuse, yet poor reporting systems and unclear guidelines prevent effective intervention, leaving its youth at risk.

03 December 2025

Since 2020, the ICPV has worked to improve drug safety reporting at Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez, with promising outcomes.

16 October 2025