Daniel Okeowo

@DanielOkeowo2

Doctoral Training Fellow, NIHR Yorkshire and Humber Patient Safety Translational Research Centre, University of Leeds

Illustration: Composite, Mariusz Slonski & Analuisa-Gamboa, Unsplash

With multiple medicine use on the rise, a UK study has set out to gather evidence for safer practices to get patients off the drugs they no longer need.

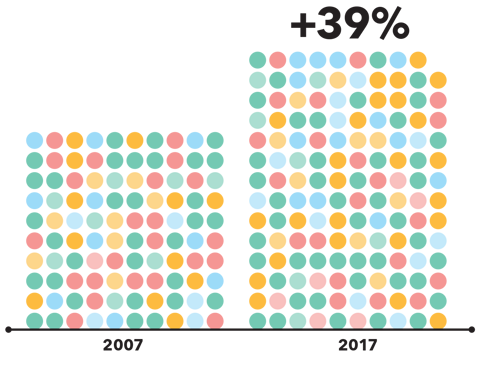

Medicine use continues to rise globally. The UK witnessed a 39% increase in the number of medicines dispensed from 2007 to 2017, and this growth does not look likely to stop. Our improved ability to understand, diagnose, and treat conditions has allowed for global improvements to healthcare and has led to more medicines being available to treat different conditions. Consequently, many patients are now living longer and taking medicines for multiple conditions, giving rise to an increase in polypharmacy (the concurrent use of five or more medicines).

Polypharmacy is not an inherently bad thing. Multiple diseases in a patient require multiple treatment plans, leading to multiple medicines used. Clinicians may also prescribe medicines to treat side effects experienced by the initial treatment plan – known as the prescribing cascade. However, clinical practice guidelines, which govern prescribing practices, are largely based on single disease models, so many conditions are also treated in isolation, further contributing to multiple medicine use. Many patients have and will continue to benefit from taking numerous medicines to improve their quality of life, but if care is not taken to routinely assess the need for each medicine, polypharmacy can become problematic.

“From 2007 to 2017, the number of medicines dispensed in the UK rose by 39%”

Problematic polypharmacy is when multiple medicines are prescribed inappropriately, or when the intended benefit of a medicine is not realised. Examples include taking several medicines that are hazardous because of a clinical interaction (between medicines or with the body) or when the overall “pill burden” is intolerable for the patient. Problematic polypharmacy can lead to non-adherence to medicines, increased use of potentially inappropriate medicines (PIMs), adverse drug reactions, and higher care costs. In summary, patient safety is compromised once polypharmacy becomes problematic.

Deprescribing – identifying and discontinuing medicines where harms outweigh benefits – can help minimise problematic polypharmacy. It is a joint process with the patient that looks to taper or stop medicines no longer appropriate for the patient, considering their preferences, concerns, and treatment goals. Although there is a lack of large, robust deprescribing clinical trials, the effectiveness of deprescribing has been investigated. For example, a 2008 paper reviewed medicine withdrawal trials in older patients (65 years and above), and found evidence for the effectiveness or lack of significant harm when antihypertensives, benzodiazepines, or psychotropic medicines were withdrawn. Similar reviews have noted deprescribing of long-term medicines appears safe, but there is a risk of relapse of symptoms that should be considered. Overall, deprescribing has shown effectiveness in medicine withdrawal trials, but is not without its own risk. Adverse drug withdrawal events are symptoms associated with stopping a medicine and may occur during deprescribing. Although this is not inevitable, it provides reason to ensure deprescribing occurs safely.

Much of the current deprescribing in clinical practice is reactive, such as stopping a medicine once a patient has already developed side effects. But there is also a need for proactive deprescribing that looks to stop unnecessary medicine use before patients experience negative outcomes. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of evidence on how to implement proactive deprescribing into current healthcare. Research has already highlighted obstacles that may impede doctors and patients being involved in deprescribing, such as fear that deprescribing is perceived as an abandonment of care, or recurrence of the original disease. Yet there is little out there on how to overcome such barriers and develop a system of safe and routine deprescribing.

“We want deprescribing to work for patients – understanding what education and support they need, whilst not compromising clinicians’ workload”

This is the motivation for our current research project at the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Yorkshire and Humber Patient Safety Translational Research Centre and the University of Leeds. We aim to investigate how we can implement safe and routine deprescribing in primary care. We want to understand the views of patients and clinicians on what we need for this to happen. This stakeholder engagement is important as we want deprescribing to work for patients – understanding what education and support they need, whilst not compromising clinicians’ workload. We are also interested in the role of community pharmacists in deprescribing. Pharmacists are experts in medicines and appear beneficial within deprescribing research, and community pharmacies are where many patients frequently receive medical advice because of their ease of access. However, little is known about the role of community pharmacists in deprescribing in primary care.

Once we understand this data, we will co-design resources with patients and clinicians that support safe and routine implementation of deprescribing in primary care. These resources will be based on implementation strategies and may be delivered as patient resources, clinician resources, pathways, or processes. We want to disseminate these findings to increase awareness on what deprescribing is, its importance and benefits, how it can be introduced into current healthcare and the role of pharmacists in this. We hope this will get the ball rolling on deprescribing implementation research and, eventually, safe and routine deprescribing in primary care.

MUEs are typically used to improve the safety of drugs, however, may they also have a role in measuring the adherence to risk minimisation measures?

06 August 2025

While underreporting remains a persistent global challenge, innovative approaches are showing promise in different regions

18 February 2026

Online psychedelic forums hold untapped safety data. AI analysis of user narratives could help pharmacovigilance systems detect risks missed by traditional reporting.

13 November 2025