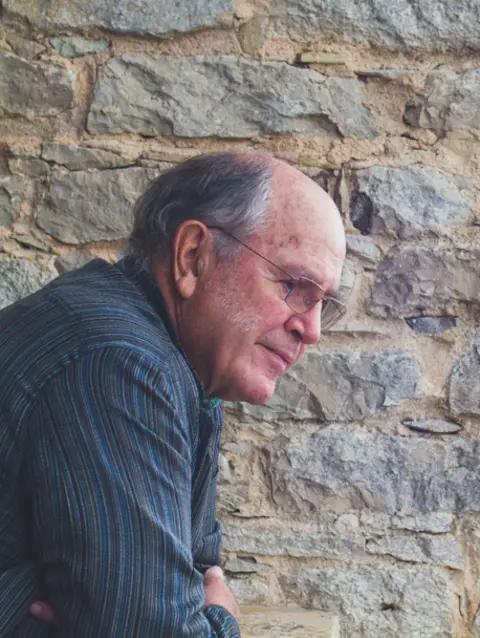

For UMC’s former, long-standing director, Professor Ivor Ralph Edwards, the road to pharmacovigilance started in Africa. So, it was fitting that an African university has now paid tribute to his work with the award of an honorary doctorate.

In November 2019, the University of Benin (UNIBEN), Nigeria awarded Ralph Edwards an Honorary Doctor of Science Degree – an honour that UNIBEN typically bestows only once every six years – at a ceremony where Edwards delivered the convocation lecture on the role of individual professionals in contributing to society.

Edwards has long, deep connections within the Nigerian public health community. In particular, his influence has helped guide and inspire the work of some of Nigeria's most significant patient safety advocates. With this award, UNIBEN recognised his primary role in the growth of science and the professional practice of the international pharmacovigilance network.

But it all started in another university, in a far-distant part of the continent, almost four decades earlier.

It was as a professor of medicine at the University of Zimbabwe in the early 1980s that Edwards first became interested in the toxicology of medicines and other chemicals. In that role, he regularly encountered cases of Stevens-Johnson syndrome – the severe, sometimes fatal, skin reaction – along with many other drug-related problems.

“I was seeing chemical injuries... including adverse drug reactions, as a major part of medicine for the first time in my life.”

“I saw one of these patients every month, whereas normally you would see one case in a lifetime in Europe,” Edwards said. “Frequently it was as a reaction to drugs that I never thought caused that problem.”

And it wasn’t only medicine-related problems that caught Edwards’ attention. Chemical poisoning, due to poor labelling or ill-informed practices, was also widespread.

“All that made an impact on me. I was seeing chemical injuries, in a broad sense, including adverse drug reactions, as a major part of medicine for the first time in my life.”

These experiences proved formative, eventually leading Edwards to the role of director of the New Zealand National Toxicology Group, which in turn led to his appointment as the first full-time director of UMC in 1992.

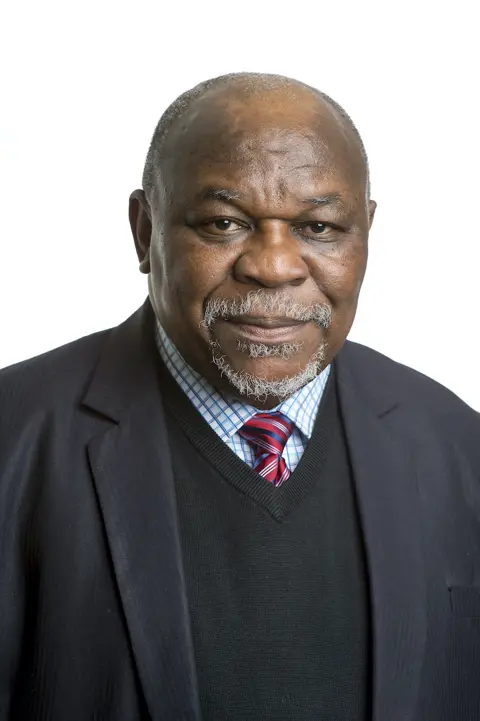

Shortly after he started at UMC, the organisation held a training course. One of the attendees was Ambrose Isah, now a professor of medicine at UNIBEN, and the two have been friends and scientific collaborators ever since. Isah, using the knowledge and connections he developed through the UMC training, became a pioneer of pharmacovigilance education and science at UNIBEN and was instrumental in establishing regulatory controls on medicines through the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC).

Edwards and UMC also formed close relationships with Emmanuel Okoro, professor of medicine at Ilorin University, and the late Professor Dora Akunyili, director-general of NAFDAC from 2001-2008. Ultimately, it was the influence of Isah, Okoro, and Akunyili that led to UNIBEN honouring Edwards.

“Certainly, it was UMC that ought to be awarded the honour, not me,” Edwards said of the impact that UMC was able to have on the work of his Nigerian peers.

“All three of these people have developed an international reputation in part because they’ve been able to talk in various meetings under the UMC umbrella and they’ve also been able to aid the WHO in their work throughout the world.”

“Ralph practically crafted the discipline of pharmacovigilance."

Isah concurs with this view of UMC’s role. Quoted in UMC’s 40th anniversary history Making Medicines Safer, he explained that UMC’s training programme “was absolutely key in the early stages of our work to set up a system for pharmacovigilance”.

“UMC has been the engine room for pharmacovigilance in Africa,” Isah said. “It has deployed a commendable arsenal of methodologies, tools and experts across the continent, in a proactive and systematic way. Africa owes UMC for bringing it into the international medicines safety community.”

But Isah also recognised the vital role of Edwards’ leadership.

“Ralph practically crafted the discipline of pharmacovigilance. He’s a really charismatic leader,” Isah said.

Since those early days, Edwards has followed closely the progress of pharmacovigilance across Africa. South Africa was one of the early leaders, with the regulatory authority delegating pharmacovigilance work to the clinical pharmacology departments of all of the universities, with a data collection centre in Cape Town.

“This was very interesting and thoughtful because you placed the primary collection centres in universities, feeding into the national collection, with review by a group of professional clinical pharmacologists who advised the major government regulatory authority about risks,” Edwards said, noting that tasking the work to academic centres meant the knowledge also flowed into the curriculum.

Countries, such as Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Ghana, Uganda, and Sierra Leone followed in a similar way. Ghana, in particular, demonstrated the value of a bottom-up approach, effectively using popular media to get people on board with the importance of drug safety. Zimbabwe made significant strides, pushing for a pan-African pharmacovigilance group through the African Union. And Morocco adopted the New Zealand approach by making its pharmacovigilance centre also function as a chemical safety centre, which Edwards describes as a great way to maximise the value of limited medical and research resources.

If there is one thing that bothers Edwards, it is that the work of UMC and the development of pharmacovigilance have not yet been given their full due in either the scientific community or industry.

“We were the first to use artificial intelligence to analyse the vast amounts of data we hold,” he said. “We have invented various tools to analyse the data. And we started the shift in focus from drug safety to patient safety.”

“I don’t think I’m at all a proud man, but I am proud to see UMC’s achievements recognised by a very good African university that understands the value in what we have done and the impact we have had on the safety of patients.”