George Sabblah

Head of Safety and Monitoring Department, Ghana FDA

With low reporting of medication errors in Africa, understanding the scale of the problem and the reasons behind it should help in efforts to improve the situation.

Medication errors (MEs) can occur at any stage of the medication use process. Globally, medication errors are estimated to cost 42 billion USD annually.

Considering the economic and social burden of MEs, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched a global campaign – the Global Patient Safety Challenge – in March 2017, the third of its kind, aimed at worldwide commitment and action to reduce by 50% medication-related harm due to weaknesses in healthcare systems by 2022.

Achieving this has become increasingly important in Africa since WHO projected that the continent bears 24% of the world's burden of disease, and that noncommunicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer, are predicted to overtake infectious diseases as the leading causes of death in Africa by 2030. Additionally, a United Nations report estimates that between 2015 and 2050, over half of the expected global population growth will be in Africa and by 2050 1 in 4 people on earth will be African. Both developments will bring with it increased use of medicines in the home over the coming years.

Given the important role of patients in medicines safety, including reporting medication errors, it is important that systems are established in African countries to enable patients to report all medication safety issues, including errors for appropriate regulatory action, to protect public health and safety.

A mixed-methods sequential explanatory study was carried out to describe the systems in Africa for spontaneous reporting of MEs and characterise the profile of MEs submitted to VigiBase. The study also identified the gaps and facilitators for reporting MEs and the potential role of patients.

The quantitative part of the study characterised the profile of spontaneously reported MEs submitted by African countries to VigiBase, while the qualitative part explored the systems for reporting MEs, reasons for low reporting, the current level of patient involvement, and facilitators to improve reporting. The link between the quantitative and qualitative studies was established in the way that the participants in the interviews in the latter part were asked to reflect on the findings from the number of ME reports received from African countries and the systems put in place for submitting such reports.

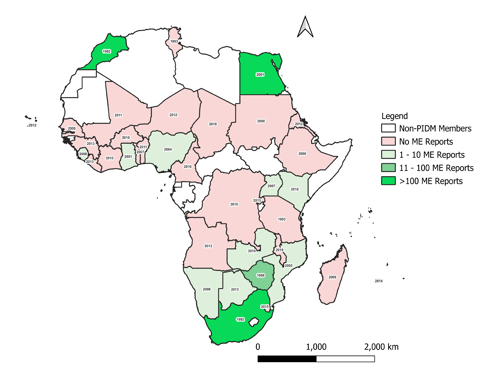

From the study, there were 4,205 ME reports from African countries submitted to VigiBase. These reports represented only 0.4% of ME reports submitted globally from other countries in the database. It was found that out of the 37 African countries that were members of the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring (WHO PIDM) as of December 2020, only 15 (40.5%) had contributed ME reports to VigiBase with 99% (3,874) of these coming from three countries, namely Egypt, Morocco, and South Africa. The 15 African countries that have submitted ME reports to VigiBase as of December 2020, the number of ME reports submitted, and the year of joining the WHO PIDM is shown in Figure 1.

The top five MEs reported by MedDRA preferred term were inappropriate schedule of product administration (496, 11.6%), incorrect dose administered (476, 11.1%), wrong product administered (314, 7.3%), product administration error (286, 6.7%) and product prescribing error (267, 6.2%). The most commonly reported medication classes with the most commonly reported errors classified by the second-level ATC codes were drugs used to treat diabetes (949, 13.3%), antineoplastic agents (648, 9.1%), analgesics (507, 7.1%), antibacterials for systemic use (441, 6.2%), and psycholeptics (311, 4.4%). The mean age of those who experienced MEs was 29.4 years (SD± 23.8). The percentage of MEs in children younger than 17 years was 32.8% (19.8% of these were infants and children below 5 years of age and 13.0% 5-17 years); 38.9% of the MEs occurred in adults between 18 and 64 years and 8.3% in the elderly (over 65 years of age). For 20.0% of the MEs, the patient's age was unknown.

“Representatives from the national centres interviewed acknowledged that there is a need to improve medication error reporting systems by suggesting ways to improve reporting.”

In the qualitative study, 20 senior officers from national pharmacovigilance centres in Africa were interviewed about the possible reasons for the low reporting of MEs on the continent. The reasons given included weak healthcare and pharmacovigilance systems, lack of capacity among staff at the national centres, illiteracy, language difficulties, and sociocultural and religious beliefs. For instance, one respondent stated, “People, maybe men in the family, if you tell him that you have made the kind of ME, she will be blamed by her husband.” Additionally, it was mentioned that most Africans believe that things happen because God allows it, so they will not report any harm suffered from ME because of the belief that it is an act of God. Another participant also acknowledged that “I think in Africa a lot of people think that everything happens because God accepts it”.

Representatives from the national centres interviewed acknowledged that there is a need to improve ME reporting systems by suggesting ways to improve reporting. These included proactive engagement of patients on issues relating to MEs, increasing use of technology, benchmarking, and mentoring by more experienced national centres.

The study also scrutinised existing systems for reporting MEs in the 20 countries interviewed. We found that 16 countries had systems for reporting MEs integrated into adverse drug reaction reporting, with minimal patient involvement in seven of these countries. Patients were not involved at all in the direct reporting of MEs in 13 countries.

This situation is worrying and points to the need to establish effective systems for patients to report MEs as part of pharmacovigilance activities. Our study, therefore, added new dimensions to the reasons for low reporting of MEs, which until now have not been reported in the literature.

In an ongoing study to explore the magnitude of MEs by carers of paediatric patients at home we found that MEs are common but some parents have innovative ways to prevent these errors, such as placing a paper sticker on the medicine label to remind them about what time the next dose should be administered.

Spontaneous adverse event reports pose significant challenges to pharmacovigilance scientists. How may we turn them into opportunities that benefit our pharmacovigilance systems?

04 June 2025

Online psychedelic forums hold untapped safety data. AI analysis of user narratives could help pharmacovigilance systems detect risks missed by traditional reporting.

13 November 2025

MUEs are typically used to improve the safety of drugs, however, may they also have a role in measuring the adherence to risk minimisation measures?

06 August 2025